When you are considering giving up some of your pieces for some of your opponent's, you should think about the values of the men, and not just how many each player possesses. The player whose men add up to a greater value will usually have the advantage. So a crucial step in making decisions is to add up the material, or value, of each player's men.

The pawn is the least valuable piece, so it is a convenient unit of measure. It moves slowly, and can never go backward.

Knights and bishops are approximately equal, worth about three pawns each. The knight is the only piece that can jump over other men. The bishops are speedier, but each one can reach only half the squares.

A rook moves quickly and can reach every square; its value is five pawns. A combination of two minor pieces (knights and bishops) can often subdue a rook.

A queen is worth nine pawns, almost as much as two rooks. It can move to the greatest number of squares in most positions.

The king can be a valuable fighter, too, but we do not evaluate its strength because it cannot be traded.

Example A

Black to move

Here's a harder problem that requires you to use several of the tips you've read about so far. Pretend you're playing black in this position. First of all, what is white's threat? Second, what move should you make to meet this threat? Finally, if white went ahead with his "threat" even after you move, what would be the result?

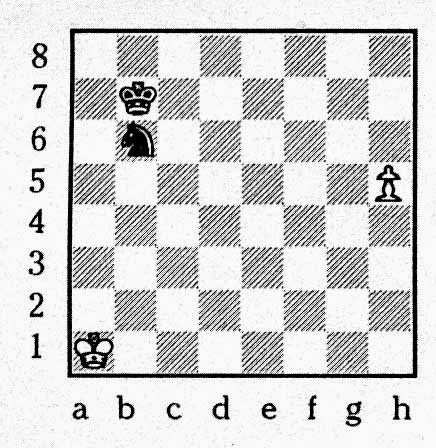

Example B

We know that a knight and a bishop are usually worth about the same. Which would you say is stronger in this position?

Example C

White to move

White is about to make a move here. Is the black knight strong or weak? Would it be better or worse to have a bishop on that square?

Answers:

Example A: White's threat here is to play Nxf7, with a double attack on black's queen and rook. Black should simply castle (0-0). Now if white continues with his "threat," black merely captures the knight and the bishop. That continuation would be

1. . . . 0-0 2. Nxf7 Rxf7 3. Bxf7+ Kxf7

You can see that white has traded bishop and knight for black's rook and pawn. That's about an even exchange, except---in the early part of the game especially---these two pieces are often handier than the rook. Note that white has exchanged his only developed pieces, while black has a bishop and two knights ready to attack.

Example B: Here is an example where a knight is better than a bishop. The bishop is trapped behind its own pawns, while the knight is free to hop in and out of black's position. It will be easy to maneuver the knight to f6, and if black defends the pawn at h7 with his king, white's king will enter black's position by way of c5 or e5, with decisive effect.

Example C: The tables turn; black's knight moves so slowly that after 1. h6, the pawn cannot be prevented from reaching the eighth rank and being promoted. If black has a bishop on b6 instead of the knight, he could answer 1. h6 with 1. . . . Bd4+, when the bishopwould control the crucial square h8.